There are many ways to attend to our patients in clinic. We can work through mental models that we’ve acquired from our schooling, study, and clinical experience. We can also use our innate human ability to touch, palpate and sense.

In this episode with Chip Chase we discuss the importance of down-regulating our nervous system. Along with the use of palpation and sensing references to anchor our ideas about what might be going on for a patient, and to track the progress of the treatment as it unfolds.

Additionally we touch in on the use the eight extraordinary vessels and their relation to internal cultivation, take a look at the relatively new emergence of using the divergent channels, and discuss the difference between intending and attending during the treatment process.

- What it means take qi seriously.

- The importance of down regulating our own nervous system.

- How action happens against a background of stillness.

- Building a palpatory vocabulary.

- The recent archeological find has the Dao De Jing not starting with “The Dao that can be named is not the true Dao,” but rather “First there are fluids.”

- Dao De Jing is a Chinese book that transcends culture

- The ways in which not-doing is not the same as not paying attention.

- The importance of settling, suppling, integrating and opening when attending to the engagement of vitality

- How with practice the yang qi of the body is palpable, as are the fluids.

- The eight extraordinary vessels and internal cultivation.

- The lack of historic reference to the channel divergences, and the relatively recent emergence of their use in clinical treatment.

- The difference between trying to attend to the patient’s qi with our attention as opposed to our intention.

Anything worth taking seriously is worth examining critically. If you have the courage to try to disprove your fondly held ideas, then you’ll find you arrive at the right approach more quickly.

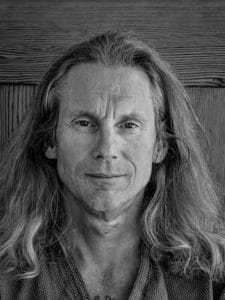

The guest of this show

My abiding interest is in the dynamic between clinical practice, textual analysis and palpatory experience. I’ve spent the past 30 years studying the pre-modern Chinese literature and trying to bring it to life in my practice. In the process, I’ve done a far amount of translation work, most notably the first textbook of acupuncture from 100 C.E., from 100 C.E., The Yellow Emperor’s Systematic Classic of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (Huang Di Zhen Jiu Jia Yi Jing) with Yang Shouzhong, and with Miki Shima, Li Shizhen’s Qi Jing Ba Mai Kao, the seminal text on the extraordinary vessels.

My abiding interest is in the dynamic between clinical practice, textual analysis and palpatory experience. I’ve spent the past 30 years studying the pre-modern Chinese literature and trying to bring it to life in my practice. In the process, I’ve done a far amount of translation work, most notably the first textbook of acupuncture from 100 C.E., from 100 C.E., The Yellow Emperor’s Systematic Classic of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (Huang Di Zhen Jiu Jia Yi Jing) with Yang Shouzhong, and with Miki Shima, Li Shizhen’s Qi Jing Ba Mai Kao, the seminal text on the extraordinary vessels.

Textual study can be very abstract and intellectual. Palpation is a way for me to ground those heady ideas in something I can touch and feel. The first class that I took when I got out of acupuncture school in 1984 was in cranial osteopathy. It was immediately apparent to me that osteopathic palpatory sensibilities have a lot to offer the practice of Chinese medicine. I’ve been exploring that ever since, most notably in the Engaging Vitality work that Dan Bensky and Marguerite Dinkins and I have been developing. We now teach this approach in the US, Europe and Australia.

I’ve been a meditator since I was 18 and this has nurtured a long-standing interest the way that internal cultivation practices inform what I do in the clinic. The palpatory tools I’ve developed make accessible lot of material that would otherwise seem pretty abstract. That too is an ongoing area of research for me. Finally, I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time alone in the back-country. That has been a life-long practice in its own right. The older I get, the more I’ve come to realize that it's the soil in which all these other interests have grown.

Links and Resources

Engaging Vitality is a way to listen to the qi and learn to follow the intelligence of the body.

Investigating The Shape of Qi

Considerations when needling: The Pivot of Nothingness

Merging of the Ways: Understanding Channel Divergences

A Synopsis Of The Eight Extraordinary Vessels In The Chinese Literature of Internal Cultivation

Practicing Alone In The Wild