In this episode of Qiological we are taking a look at dry needling not from the legal or scope of practice point of view, but rather from the viewpoint of how acupuncturists can learn something from this form of acupuncture that has quickly grown in popularity among our conventional medicine colleagues.

We all know that acupuncture can be powerful medicine. Little wonder that other professionals would like to be able to access its healing power. And in some ways, conventional practitioners have a leg up, as they already speak the language of the dominate culture, and have a certain status due to being associated with “scientific” medicine.

In this panel discussion with three experienced and dedicated acupuncturists we explore what East Asian medicine practitioners can learn from the dry needling community.

Listen in to this conversation that is less about legalities and more about opening up an uncomfortable avenue for learning.

In This Conversation We Discuss:

- What can Acupuncturists learn from dry needling

- Overlaying the dry needling map with Chinese Medicine

- The importance of language

- The safety issue

- What do acupuncturists have to fear?

- Final thoughts and advice

The guests of this show

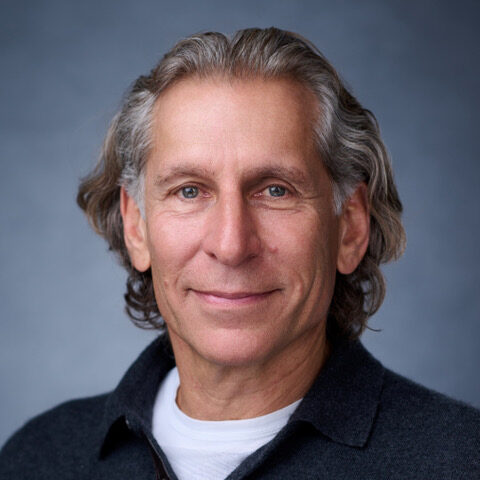

Fernando Bernall, DOM, AP, CFMP

Fernando Bernall, DOM, AP, CFMP

I'm a National Board Certified Chinese Medicine practitioner (NCCAOM), and a licensed acupuncture physician in Florida and Colorado. I hold certification in Functional Medicine as a graduate of the Functional Medicine University.

I'm is also a member of the Institute of Functional Medicine at Cleveland Clinic.I've has completed post-graduate training in substance abuse at Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center in the South Bronx, NY. and I'm a Certified Myofascial Trigger Point Therapist (CMTPT).

Currently I employ various styles of orthopaedic acupuncture including dry needling, motor point acupuncture, and trigger point injections. I'm available for workshops, seminars and group talks.

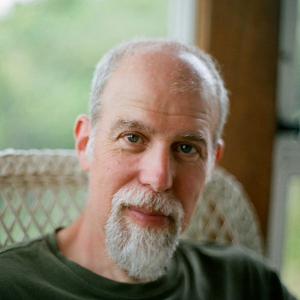

Brian Lau, AP, DOM

Brian Lau, AP, DOM

In 1998, at 28, I started studying taiji and qigong with the Taoist Tai Chi Society. I felt changes in my posture, increased movement and circulation, and a sense of more space and room in my body. Much of this was attributed to what we referred to as ‘tendon changing' – but these ‘tendons' were described as extending across vast regions of the body. Obviously, they were not tendons as described in the West. Curious, I became certified in structural integration (SI) in 2003 and undertook a deep study of fascia, a gateway to understanding the mysterious ‘tendons' discussed in my taiji and qigong practice. During this time, fascia research was blossoming; not only SI scholars but acupuncture researchers such as Helene Langevin were prominent in the growing modern awareness of the importance of this tissue. Fascinated, I earned my acupuncture degree and began practicing in 2011.

I got both more and less than I hoped for from TCM school. Hoping to build on my previous study, I instead was received into a deeper tradition, one richer than I anticipated, but which felt utterly alien to structural integration. How could two fields of study with so much in common be so different? To bridge the gap, I enrolled in Sports Medicine Acupuncture Certification and began studying with Matt Callison. I was asked to be on the faculty of this program in 2014 and am currently teaching with SMAC. Much of this work involves collaborating with Callison on building a model of the channel sinews (jingjin), based on SMAC’s ongoing cadaver studies, functional anatomy, fascial research and, of course, the descriptions in the Lingshu. This once-abandoned, long-overlooked avenue of Chinese medicine is overdue for rediscovery, and recovering and fully developing it has become my life’s work.

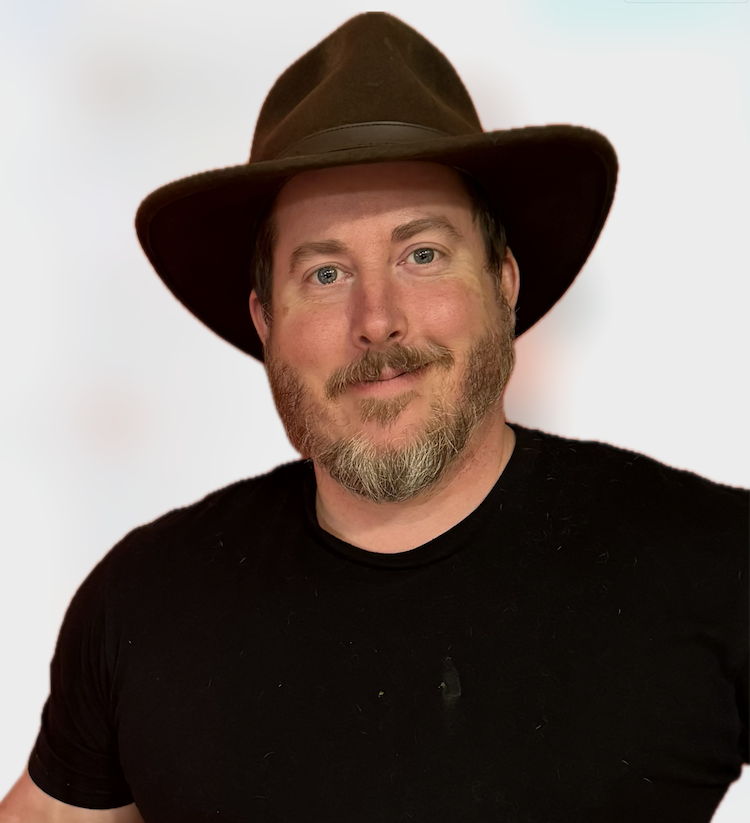

Josh Lerner, L.Ac

Josh Lerner, L.Ac

I was an Asian Studies nerd from high school through grad school, where I ended up working on a doctorate in Buddhist Studies. Realizing that I actually had no interest in an academic career, I left graduate school to become an acupuncturist, enrolling at NIAOM in 1997. My initial interests in Chinese medicine were based on my years of study of Chinese and Japanese language, Daoism, and martial arts, so I started off with a heavy interest in being a scholar/physician, combing through classical texts and using herbs to treat complex internal medicine disorders.

And then . . . I started meeting and learning from practitioners, both within the field of TCM and western medicine, who specialized in orthopedics and sports medicine; practitioners who inspired and impressed me in a way that no one else had, giving me the feeling of “Wow, that’s who I want to be when I grow up.” There were many acupuncturists with martial arts backgrounds who specialized in tuina and other forms of manual medicine, physical therapists, occupational therapists, osteopaths, and chiropractors. I ended up falling in love with the immediacy and demanding intricacy of orthopedic and manual medicine. So now I combine acupuncture, tuina, other forms of manual medicine, herbs, and physical movement practices with all of my patients while I continue to discover massive blind spots and gaps in my knowledge that require further learning and study.

In 2010, I was given the opportunity to start teaching at the Seattle Institute of Oriental Medicine (now the Seattle Institute of East Asian Medicine), where I continue to learn about how blurry the line is between teaching, clinical practice, and personal cultivation.