Tools in East Asian medicine are not just inanimate objects. They are a tangible extension of the healer's touch, a conduit for their energy and intention to flow through. Our tools are essential for turning stagnation into flow, pain into ease, and the discordant notes of illness into wellness.

And while the true power of our medicine lies in the practitioner’s ability to evoke the body’s innate capacity for balance and harmony, the tools are essential to the work. And fine tools are a joy to use.

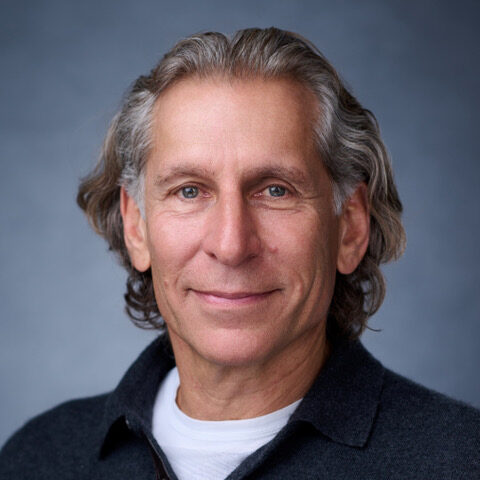

In this conversation with Kevin Ferst, he walks us down the unexpected path that brought him to working with local artisans in the crafting or vessels for healing in the remote Appalachian mountains of New York. We explore the nuances of cup making, from the intricate art of glassblowing to how the quality of the tool makes a difference in the clinical experience of both the patient and the practitioner.

Listen into this discussion on creating and using quality tools, and a glimpse into the complexity and challenge of designing and bringing to market handmade cups from rural USA.

In This Conversation We Discuss:

- Alfred, New York – The small village where it all started

- How Kevin Ferst got interested in making cups

- The process of blowing glass with integrity

- The role of the glassblower’s mind and intention in making a good cup

- Cupping as a gourmet experience

- Being part of the solution as an entrepreneur – making your community a little greener

- Designing cups with a magical degree of flare

- Running cupping

- Listening hand – Cupping as a diagnostic tool

- “How do people get hold of these cups if they want one?”

As an acupuncturist, when it comes to any manual therapy outside of the practice, my go-to is usually cupping. I find myself using it more often than not before any other technique.

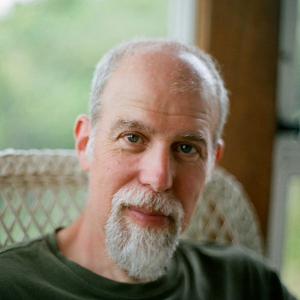

Kevin Ferst is a Nationally Board Certified in Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (NCCAOM). He served Western New York for many years, starting his practice in underserved rural communities in the Southern Tier of New York where he became adept at treating severe and chronic cases. He was on Staff at Jones Memorial Hospital / University of Rochester in Wellsville NY. And has lectured across the region at places like Alfred University, the David Howe Public Library, the Mildred Milliman Cancer Treatment Center, Jones Memorial Hospital and spoken to community and service groups.

Kevin Ferst is a Nationally Board Certified in Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (NCCAOM). He served Western New York for many years, starting his practice in underserved rural communities in the Southern Tier of New York where he became adept at treating severe and chronic cases. He was on Staff at Jones Memorial Hospital / University of Rochester in Wellsville NY. And has lectured across the region at places like Alfred University, the David Howe Public Library, the Mildred Milliman Cancer Treatment Center, Jones Memorial Hospital and spoken to community and service groups.

Kevin graduated from the Seattle Institute of Oriental Medicine, an apprenticeship training model under top physicians from China, Taiwan, and Japan. He studied an eclectic variety of different treatment modalities which he uses in the clinic today. Cupping is one of his favorite therapies, which over many years led him to develop the handmade cups, proudly made in Alfred NY.

Kevin pratices in Bedford, NH at Perfect Point Acupuncture. https://perfectpointacupuncture.com/

Links and Resources

Professional Grade, artisan cupping supplies can be purchased or perused at Handmade Holistic.

Subscribe To This Podcast In Your Favourite Player

Share this podcast with your friends!

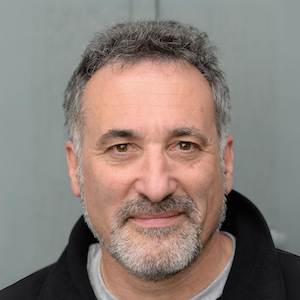

Shop Talk with Michael Max

Listening and “How of Being” in Clinic

In this Shop Talk segment we discuss the multi-sensory aspects of listening, and begin to explore the vast topic not of the “what we do” in clinic, but instead the “how we are.”

Presence and attention, being inquisitive on behalf of our patients and keeping a rein on our ego are all skills that have nothing to do with what points we choose, and everything with how we interact with those points.

I thought I’d know a lot more after 25 years in practice, and I’ve also learned so much that I never expected.

I thought I’d know a lot more after 25 years in practice, and I’ve also learned so much that I never expected.

Over time I’ve learned to say less in clinic and to listen more. It sounds easy; it’s not. It’s not easy because it is oh so easy for the helpful spirit in me to want to be of service and ‘give something’ to my patients. It’s taken a long time to realize that attempting to give something to a patient that they did not want or ask for was a burden to them, and a waste of time and breath for me.

Over time I discovered that getting still and seeing if I could understand my patients from their point of view, if I could connect with the kind of empathy that seeks first to understand, or if I could patiently wait for a patient to tell me what they actually needed, it seemed to help. It made diagnosis easier, and my treatments more precise.